|

|

the-south-asian.com April 2005 |

|

|||

|

April

2005 Archaeology

Music

Books Between

Heaven and Hell

|

|

||||

|

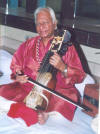

Pandit RAM NARAYAN - BOWING TO SUCCESS by Surabhi Khosla

The strings of the sarangi come alive when Pandit Ram Narayanís fingers glide over them. And no matter how disillusioned he is with his own country, this great musician might yet convert the fading sarangi into Indian classical musicís shining beacon. He is the maestro of sarangi - an ancient and difficult string instrument in classical music. For years now he has enthralled audiences around the world with his creativity. His extensive experimentation and research with the structure of the instrument has resulted in invaluable modifications that have made it easier to handle. In fact so innovative have been his changes that they are now considered established standards in all concerts. Pandit Ram Narayan has become almost synonymous with the instrument he plays. Recently aficionados had the rare occasion of watching him perform at the 33rd ITC Sangeet Samelan, and almost Zen-like become one with his sarangi. But, unlike the esteem showered upon him by music lovers, Pandit Ram Narayan has always carried a chip on his shoulder. He has perpetually complained that India has never given him the recognition he deserves. And this, despite the string of honours including the Sangeet Natak Academy Award, Kalidas Samman and this year the highest civilian award---the Padma Bhushan. But he has a problem with that as well. "Many people feel that the Padma Bhushan award has come too late in the day." And then he adds quickly, "I have always played my music with devotion and awards hold no meaning for me." He says that he has always got more appreciation in Western countries. "My overseas tours have given me confidence and financial stability." Born in Udiapur, Rajasthan, Pandit Ram Narayan descends from a family of five generations of exceptional vocalists and instrumentalists. His formal training in music started at age seven under many specialists such as Ustad Mehboob Khan, Pandit Udayalal, Pandit Madhav Prasad and Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan. By the time he was 14, Narayan had already mastered an instrument which dates back to the earliest known music forms in Indian music history. Sarangi Shahenshah His talent was such that while he was a teenager, he was assigned a job as a staff artist at the All India Radio. He began his career as an accompanist to various vocalists, and soon earned the sobriquet of a sarangi shahenshah. However, Narayan had far greater plans in store for himself. "Though as an accompanist I learnt a lot from other vocalists, I wanted to go into the unexplored possibilities of the sarangi and make it more popular," says he. Unfortunately, the sarangi, relegated to the role of an accompanist, did not occupy a place in classical music until the last few centuries. This less important role of the instrument imposed many restrictions on the Panditís noble ideas of studying and promoting his music further. Not one to be daunted, he decided to break free of the stigma and perform as a solo artist. His perseverance paid off in 1957 when a performance endeared him to thousands of music lovers and made classical musicians and critics sit up and take note. "It was truly a momentous moment for me," says Pandit Narayan, Though he has given innumerable memorable performances in the East and the West alike, Pandit Ram Narayan does not feel much for fusion music. Fusion, he says with an endearing smile, "is confusion. One needs to focus all attention on one type of music. The sarangi has a spiritual language and one cannot fuse it with western instruments simply to increase its popularity." Which explains why he is worried about the future of the sarangi. " It is sad that a beautiful instrument like this one is being considered an endangered species," says he. He feels that to recognize the value of the sarangi, music needs to be ingrained into children at the school level. "Unless classical music is made compulsory in schools and colleges, the next generation will not take to it. All that children are exposed to today is low quality pop music. No eloquent musicians are emerging to give us poetic lyrics and lilting melodies," says he. He is also disappointed by the fact that classical music is losing its sponsors "There has been a change of scene in the last few years in India with sponsors of classical musicians becoming more and more difficult to come by." Despite the lack of sponsors and in spite of his years, Pandit Narayan shows no signs of slowing down. "There are many concerts to play at, many more people to introduce the sarangi to and many more music lovers to create," smiles he, "so how can I slow down?" Indeed, no matter how disillusioned he is with his own country and with the listening public, this great musician might yet convert the fading sarangi into Indian classical musicís shining beacon. ***** |

|||||

|

Copyright © 2000 - 2005 [the-south-asian.com]. Intellectual Property. All rights reserved. |

|||||